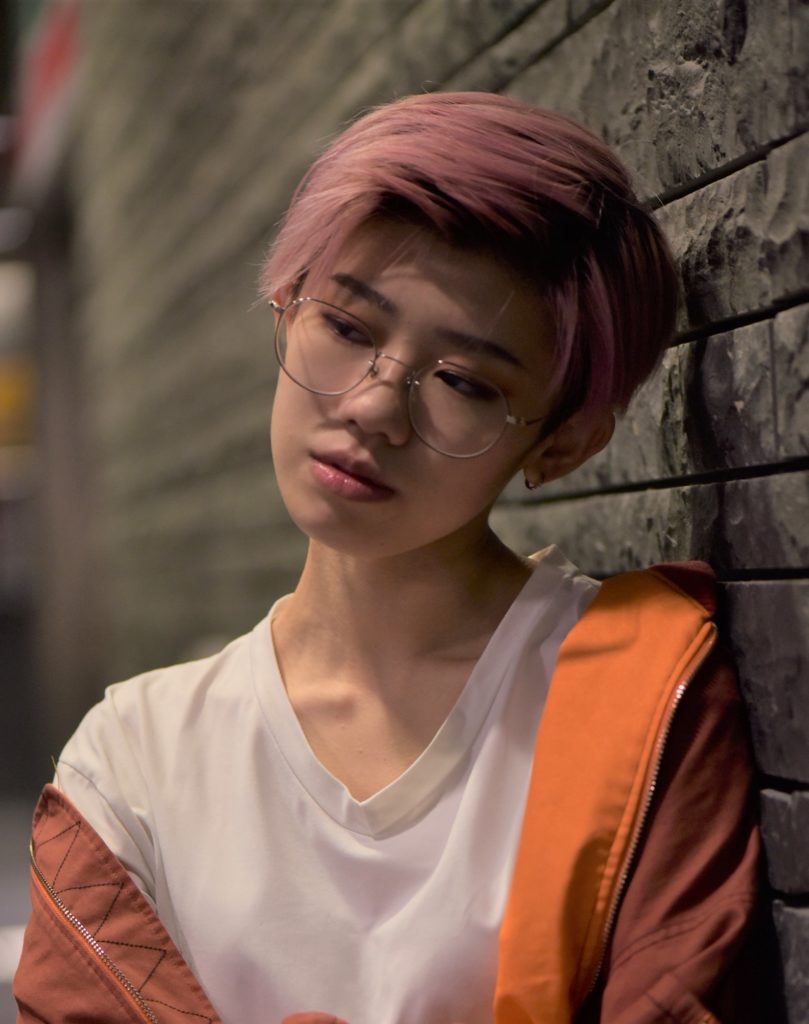

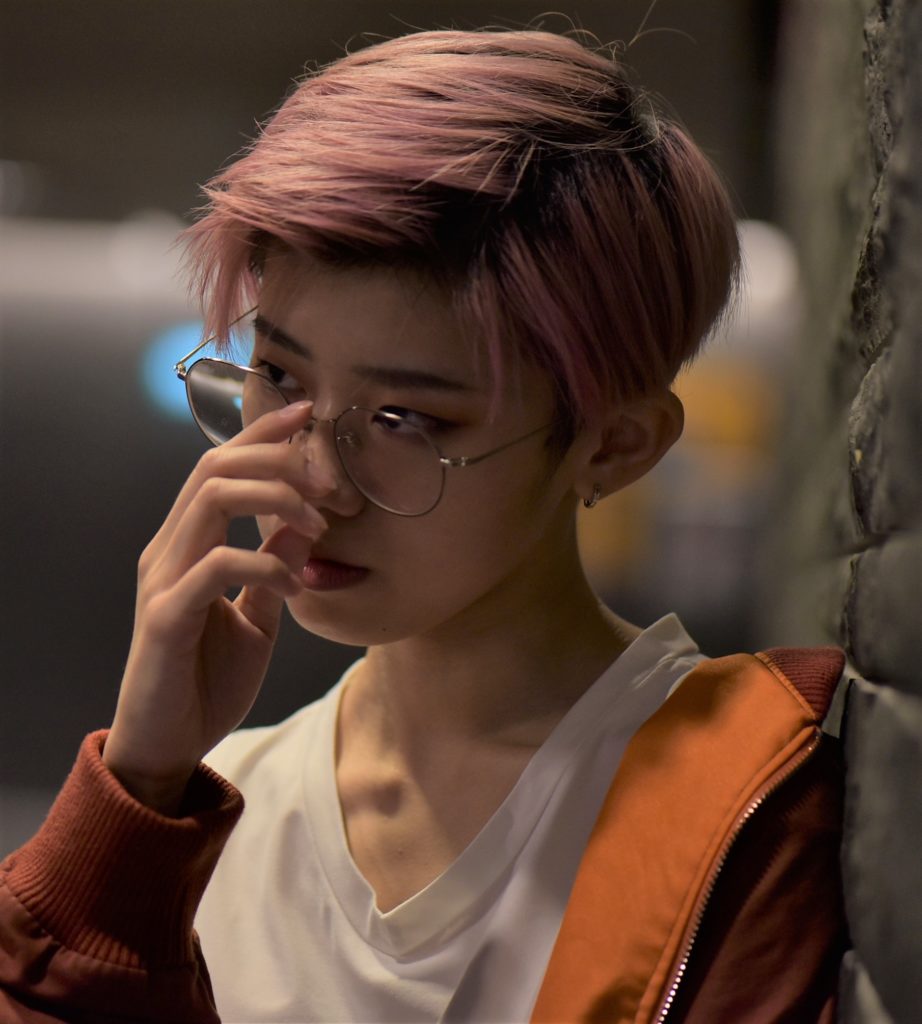

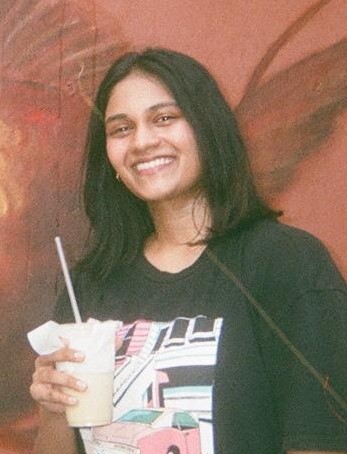

Unlocking ADHD writer Amy Sng takes us into her mind, with this personal account of her experience with ADHD and its impact on her school life, self esteem, and dreams.

This might be difficult to read. It’s certainly difficult for me to write, as much as I’m someone who lives and breathes words, sentences, books, and the like. This time, I’m on the other side of the text— I get to write my own story. Or tell it, rather.

Maybe we should start there, with books. I study them, as a literature student. Ironically enough, once I entered uni, they were the one thing I couldn’t stand. I grew up surrounded by books, taught to read wide and as deep as I wanted to. I learned most of what I know on my own, from books and searching and messing around until I got it to work. Intuition has always been my friend, but results never were. Not where it mattered. As much as I excelled in reading and seeking and learning, I always struggled with getting things done. It’s one of those things that they don’t tell you about being homeschooled, having to do things (ugh.) I had daily goals, with a designated amount of pages of each subject to finish each day. It wasn’t crazy hard; if you can read and process words on a page, you’re more than likely to be able to teach yourself. I could read, I could understand, but when I held pencil to paper, nothing would happen. Yeah, typical ADHD story, but it’s still my story.

The one thing I didn’t prep for: Uni Life

It wasn’t so much the lack of productivity that got to me. I could very much do it, in fact, I could perform miles above expectation. I crammed a whole year’s worth of daily work into three months for years and years because my mum’s only rule was that all your books need to be finished by the year’s end. Like December 31st, New Year’s Eve kind of year’s end. I finished it all, I got through high school, or what everyone else calls JC or Poly here. I got into uni after taking my SATs, where I crammed years of prep into about three or four months. It could have been less, knowing myself (ew you gremlin,) but I still got through it to land in the international top 20%. Above average. I didn’t touch any prep for my literature subject test. Easy grades. The one thing I didn’t prep for was uni life. Who knew you had to read whole novels in a week? Certainly not me. But I loved what I did. My affinity and ability for writing shone— the one thing I knew I could do. I might balk at having to multiply six by seven like the crappy arts student I am, but I can vomit an essay into your lap at the faintest glow of the shaky lightbulb in my empty skull. To wax poetic, its light is incandescent (hah). It gives me the greatest bliss in the world to look at my ideas laid out in kind-of-neat paragraphs in Times New Roman 12-point MLA format, and have people read it and grasp the tendrils of spark and inspiration that run through my brain. The thing is, you can’t write anything in this course of study without reading the blasted text that you’re supposed to write about first.

The cycle of avoidance

There’s no way to describe the helpless feeling in your chest when you watch the clock tick over to midnight and know that the entire copy of Beowulf in your cinderblock of an anthology needs to be read by the next morning. And that you’ve spent the whole day attempting to put together the words on the pages to form coherent sentences that make sense with zero success. It makes you miserable. So you do what anyone does when they feel miserable. You do Something Else. But when everything you do ends in a whole lot of Nothing, you do Something Else more and more and more and more, and if you repeat the cycle enough times, you learn that it’s always better to do Something Else. Nothing will always happen, you will always feel like you’re drowning and helpless and useless, so you might as well do Something Else. The cycle of avoidance continues, infused with looming anxiety and crippling self-loathing. The vortex grows, it consumes your sleeping hours which consume your waking hours, it eats up time with your friends (if you even have any by this point), it eats your self-worth and identity up, it eventually cannibalises the Something Else you’ve been doing the entire time, and once it’s cold and dead and gone, you seek more.

Finding the common denominator

I dragged the weight of the vortex with me for a few months. A valid attempt. I’m not a superhuman, clearly. I know it sounds dark and exaggerated, but it’s hard to tell people that you’re suffocating under the weight of your own mental paralysis when you have every reason why you should be able to read a stupid poem. How are you supposed to have people take you seriously when your only reason for not being able to Do Things is “I just couldn’t?” There’s no clear reason. The debilitating death spiral is only something I’ve seen in retrospect. In the moment, when you have to answer for your inaction, there are no words to describe it. “Lazy,” “undisciplined,” “careless,” are things I’m used to being called. Yet, I can hammer out a script for a small-scale theatre production in the span of a week, and then produce and direct it on my own. I taught myself the flute. I taught myself crochet. I taught myself almost everything I know after I was taught to read. How can I be lazy if I put work into these things to get to where I can show them off to others? Undisciplined? Careless? It doesn’t add up. What else could it be?

You.

You’re the common denominator.

Trying harder does nothing. The vortex drags you in deeper. How are you supposed to fix something you can’t even begin to point to, besides yourself as a person? It’s inherent, it’s always been there, and it won’t go away, no matter how much willpower and determination you put into it.

I got a message from a friend. Click. The shaky, tired bulb glows.

“Dude, that sounds like ADHD. You should get that checked out.”

A bumpy road to diagnosis

The shoe fits, as the idiom goes. Impulsive, distracted, inclined to mood swings from Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (or overthinking to the point of intense emotional reaction,) introverted, hyperfixated on various hobbies and interests, and would you believe it, depressed or anxious. Who knew that having zero fulfilment in the things that matter would result in depression and anxiety? It was uncanny. It was like someone had laid out my life in front of me in such specificity that you would think reptilians were probing my brain through my ears as I slept. I tried to cope on my own for a while. Would you believe it, it produced absolutely nothing. I finally sucked up the guts to ask my parents to help me get an assessment. Six months at NUH. That was just the waiting list. I went for months of psychiatrist appointments only to be prescribed Lexapro for my mood swings and to be told that I don’t have ADHD because I lack childhood symptoms. After explaining my lifelong history of symptoms to her. After she had tried to convince my parents that going on medication would mess me up if I ever did get diagnosed. Yep, she changed her advice when I kept pressing. But keep pressing I did.

My family was $800 poorer after pressing. Inconclusive results, the psychologist said. The computers don’t lie, apparently, even though ADHD isn’t a conclusive, noticeable form of inattention that spans all activities and tasks. The test treats it like your brain is just always on a short fuse, like the doctors with their expensive degrees and licences who look you in the eye and tell you that you definitely don’t have ADHD because you’re sitting down like a regular person and talking to them face to face with no obvious issues. Try telling an asthmatic that they don’t have a potentially deadly chronic illness because they’re sitting in front of you and not having an asthma attack at that very moment. I’ve experienced both, and it’s incredibly infantilising and frustrating. Except the doctor I saw for my asthma was a polyclinic doctor. I didn’t pay her over S$100 for a consult, and then S$800 for a test that doesn’t even look at ADHD symptoms in adults. I was fed up, so I left. My therapist told me to. The one good thing I had in terms of professional help.

I was referred to another doctor through my friend, even if it was more expensive than the psychiatrist at NUH for every visit. I was even prepared to pay for another expensive assessment by myself. I walked out of the clinic with the reports from the NUH assessment and a crisp prescription for Ritalin, Medikinet, and Concerta. Apparently all you have to do is find a doctor that listens to you. But it made a world of difference.

The most amazing epiphany

It was like magic. I could remember routines, I could sit down and fill out the forms I had been avoiding for months in a single afternoon, I could even process numbers at my retail job with perfect accuracy when before, I made daily mistakes that cost precious time in the middle of the lunch rush. I could even process people speaking to me better. I didn’t even know I had a problem with that until I was medicated. On top of existing medication for my anxiety and depression, my daily Ritalin caused a massive upturn in my mood. I didn’t know how badly my inactivity and inattention sucked the life out of everything I did until I could finally live without it. It was like having smudged glasses and giving them a good wipe. I could finally see for the first time in my life, I could live and breathe and not have to worry if my brain would betray me if I needed to listen to a lecture or write an important email.

It was the most amazing epiphany that I finally had an answer for so many struggles that I had experienced throughout my entire life. It was even more relieving to realise as a consequence, that all of these shortcomings were never my fault. Never. I could finally forgive myself for things that I had always blamed myself for, and make peace with myself. I could finally stop hating myself for things that I thought were etched deep into my brain and behaviour, things that I thought I would never be free from. Of course, it didn’t mean that life after Ritalin would be smooth sailing, but I finally felt like I had control back. I had the power to change all the things I hated about myself because I could focus long enough to get things done.

Then I cried.

I realised how much of my life had been swallowed up by the deep, aching helplessness of being trapped in my own mind, and how much I had lost of my younger years because I had been struggling with myself. Of course, it’s not something that can be changed. Done is done. The power to do is finally back in my hands, but it will always hit close to home thinking about how much I’ve lost to the crippling death spiral.

A definitive turning point

Things hit a definitive turning point for me, especially in school. On top of my massive improvement in mood, it was unreal to be able to sit in a lecture and process what my professor was saying in real time. Previously, I would zone out for large patches, and return to earth completely lost. Now, my mind was alert. Clear. Blissfully silent and free from the fuzziness that previously plagued me at all hours. Taking Ritalin was like being given a new brain. The best way I can provide a comparison is by saying that being unmedicated is like lucid dreaming. Ritalin is being awake. It was by no means easy to manage being in the lecture hall while on a stimulant, but I put a pair of knitting needles in my hands that I had previously abandoned, and all was good. I participated more, if not as much, as any other student with a perfectly functioning frontal lobe. My professors loved it. I loved it. Essays were easier than ever, too. I could finally work in the day instead of being forced to cram in my work in the evening through the early hours of the morning. It certainly didn’t stop my habit of overnighters, but it eased it along as my workload increased. My assignments were coming back with the straight As I knew I could get.

It’s not to say that medication magically gave me the capacity to score high grades— I was already getting them in my first semester. I even had my first academic publication in my first semester, a year before I was diagnosed. I already had the capacity for excellence, but knowing how to manage my condition allowed me to remove the barriers that made it difficult to function and perform at top condition. Think of it as a boat filled with rocks. The rocks cause resistance, and may even threaten to sink the boat if they pile too high. Take off the rocks, starting with the things you can shift, and it gets easier and easier as you go. When I finally threw off the bulk of my ADHD symptoms, my boat could float so much smoother.

Don’t delay an assessment

I think the reason why I wanted to write like this is because I want people to understand my experience. It’s the one way I can try to impress on others my struggle and the sense of relief I had when I received my diagnosis. If hearing my story resonates with you, I would encourage you to consult a professional. Don’t let it snowball until you can’t take it anymore, whether it’s ADHD or anxiety or depression. You’ll lose more than you think you might by avoiding action, and you’ll gain more than you’d think if you reach out for help. Getting a diagnosis was by no means easy, but it was the best decision I’ve made in my life. Being able to understand that there is a known reason behind my struggles and a solution that I can implement has allowed me to live much more freely and achieve the things I knew I was capable of, but could somehow never reach. If you or a loved one might be thinking of an assessment, don’t delay it. You could be making a decision that could change their life as they know it.

[If you liked this story and found it helpful, please SHARE it. For more personal stories about ADHDers, please click here. Unlocking ADHD has also organized a series of events and you can view our past webinars on YouTube. ]

Leave a Reply